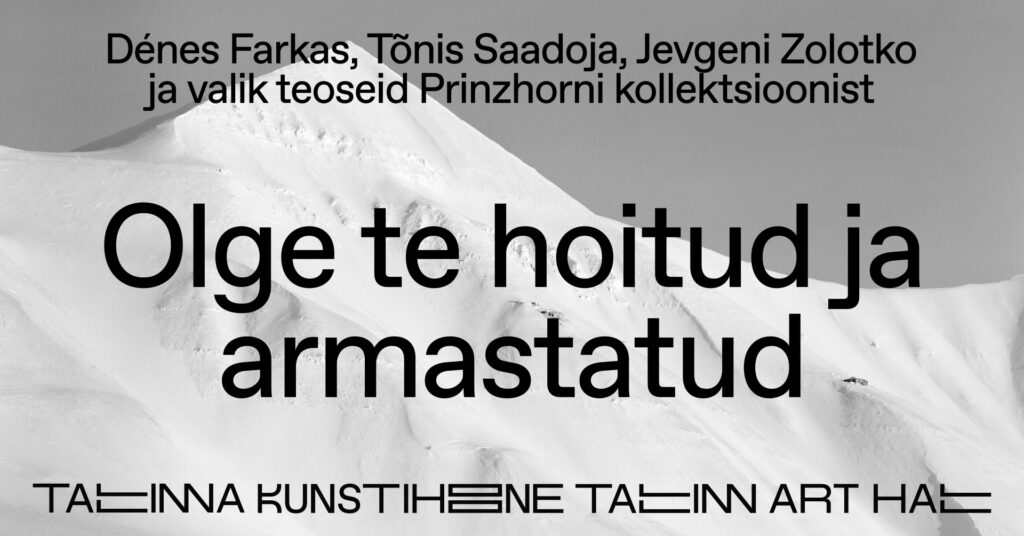

May You Be Loved and Protected

“The story of every exhibition begins with the artists that resonate with you. If there happens to be more than one, they indeed have to be excellent artists, so that their simultaneous speech does not become a hammering cacophony in your head. The experience of viewing the works by Dénes Farkas, Tõnis Saadoja and Jevgeni Zolotko has been more powerful than speech. Rather, it resembles a flood where you have to keep your mouth shut to stay afloat. ‘Our own’ Hungarian Dénes Farkas, ‘our own’ Russian Jevgeni Zolotko and ‘our own’ Estonian Tõnis Saadoja present a powerful cross-section of the modest potential of the diversity of Estonian society. In speaking about themselves, the three solitary creators also manage to speak about something much greater,” says Tamara Luuk, curator of the exhibition.

The meaning and symbolism of works on display is deeply rooted in emotional memory. They stubbornly resist all ideological connotations and the moving sands of changing interpretations. The foundation of human condition – childhood memories, feelings of fear, faith and doubt, longing for wholeness and sanity are lived by everyone, even if they are hidden in the background or in the grey areas of pragmatic, philosophical or political thought. Art is often the only place where these messages from deep inside can be expressed and where the perceived weakness becomes strength.

Estonia is one of the countries that has not yet exhibited the famous art collection of the Psychiatric Clinic of the University of Heidelberg, which includes 27,000 works: drawings, paintings, collages and handcrafted items from non-normative individuals who have not fitted into social conventions. Works by “outsiders” from the end of the 19th century to the present, gathered in the collection named after psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn, testifies to the complicated relationship between the society’s notion of freedom and that of the individual. Often the choice and condemnation of the political elite has been significantly crueller than the “natural selection”. This is evidenced by the fact that many authors of these works were killed following the prescriptions of the Aktion T4 euthanasia program of Nazi Germany. The term “insane beauty”, used by cultural institutions of several countries in relation to films and exhibitions introducing the works from the Prinzhorn Collection, has had a disturbing effect and has motivated the abuse of power – not only in the past and not only in Germany.

At a time when society is reviewing its survival strategies and moving towards greater isolation, this exhibition is dedicated to art that hurts and also heals, and to the artists who give shape to things and make them visible.